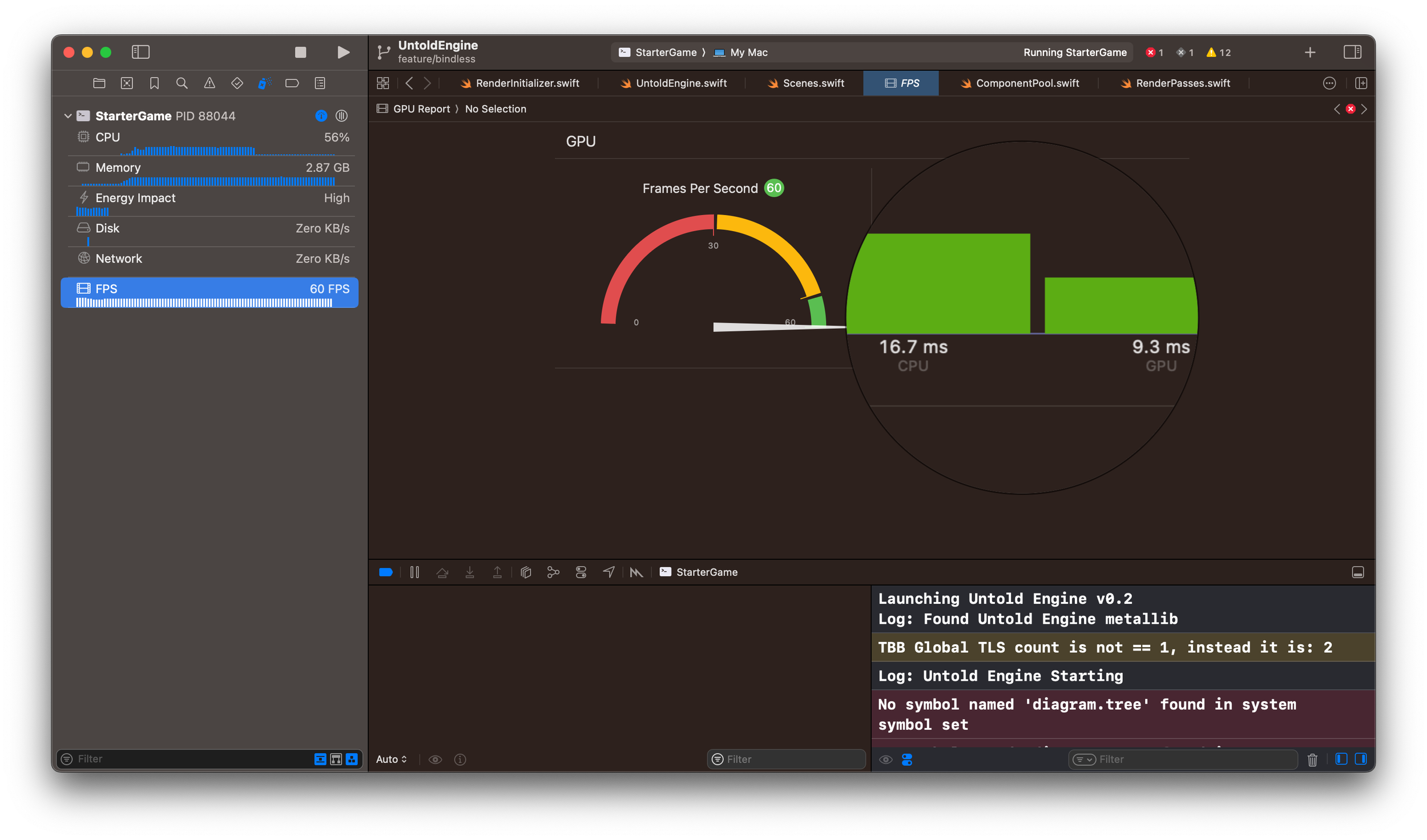

I found a bug in the Untold Engine in the weirdest way possible. After merging several branches into my develop branch, I decided to run a Swift formatter on the engine. Three files were changed. I ran the unit tests, they all passed, and then I figured I’d do a final performance check before pushing the branch to my repo.

So, I launched the engine, loaded a scene, and then deleted the scene.

The moment I did that, the console log started flooding with messages like:

- Entity is missing or does not exist.

- Does not have a Render Component.

This was the first time I had ever seen the engine behave like this when removing all entities from a scene. My first reaction was: the formatter broke something.

But the formatter’s changes were only cosmetic. There was no reason for this kind of bug.

At that point I was lost. So, I asked ChatGPT for some guidance, and it mentioned something interesting: maybe the formatter’s modifications had affected timing. That hint got me thinking.

After tinkering a bit, I realized the truth: this bug was always there. The formatter just exposed it earlier.

The Real Problem

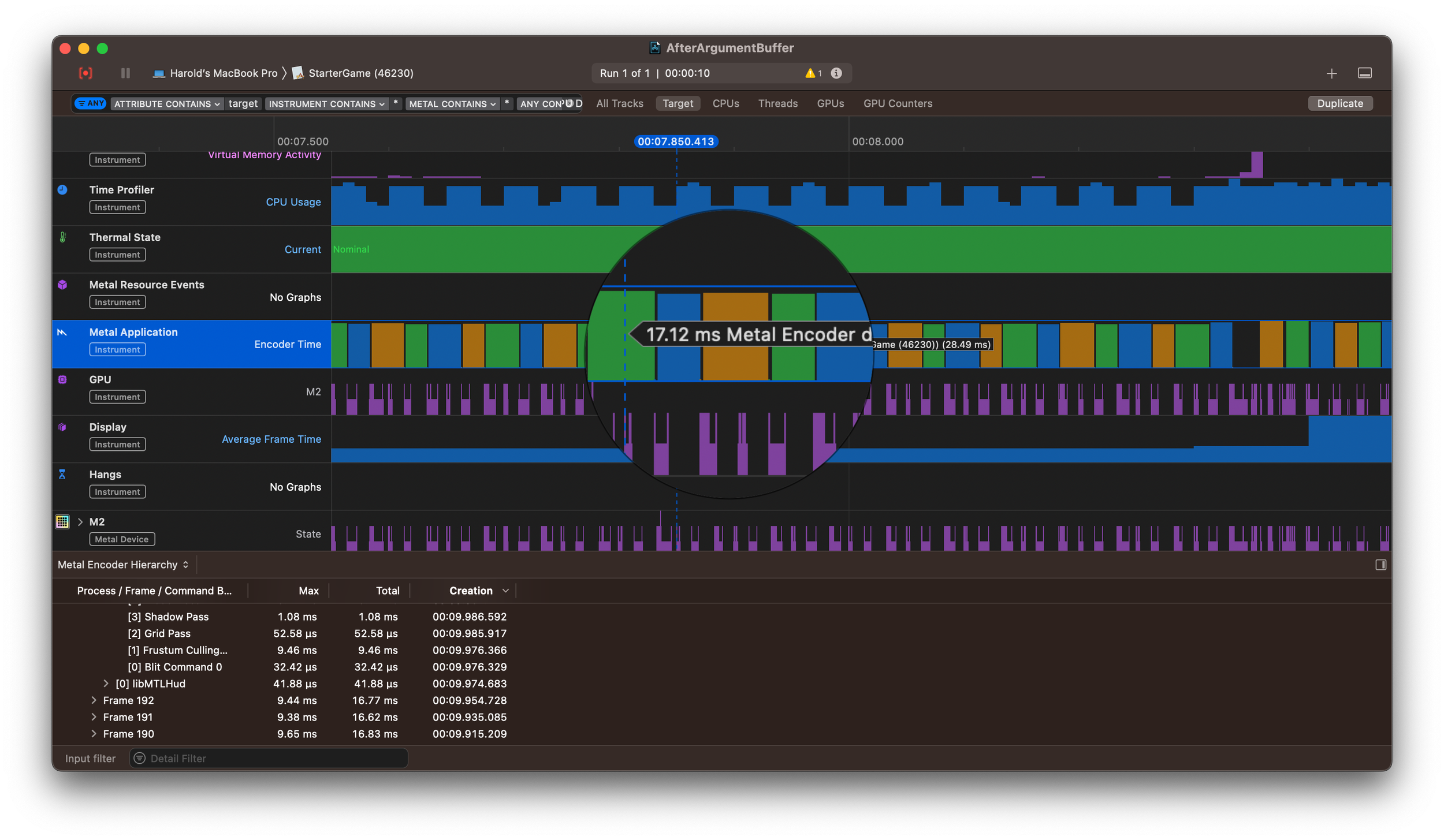

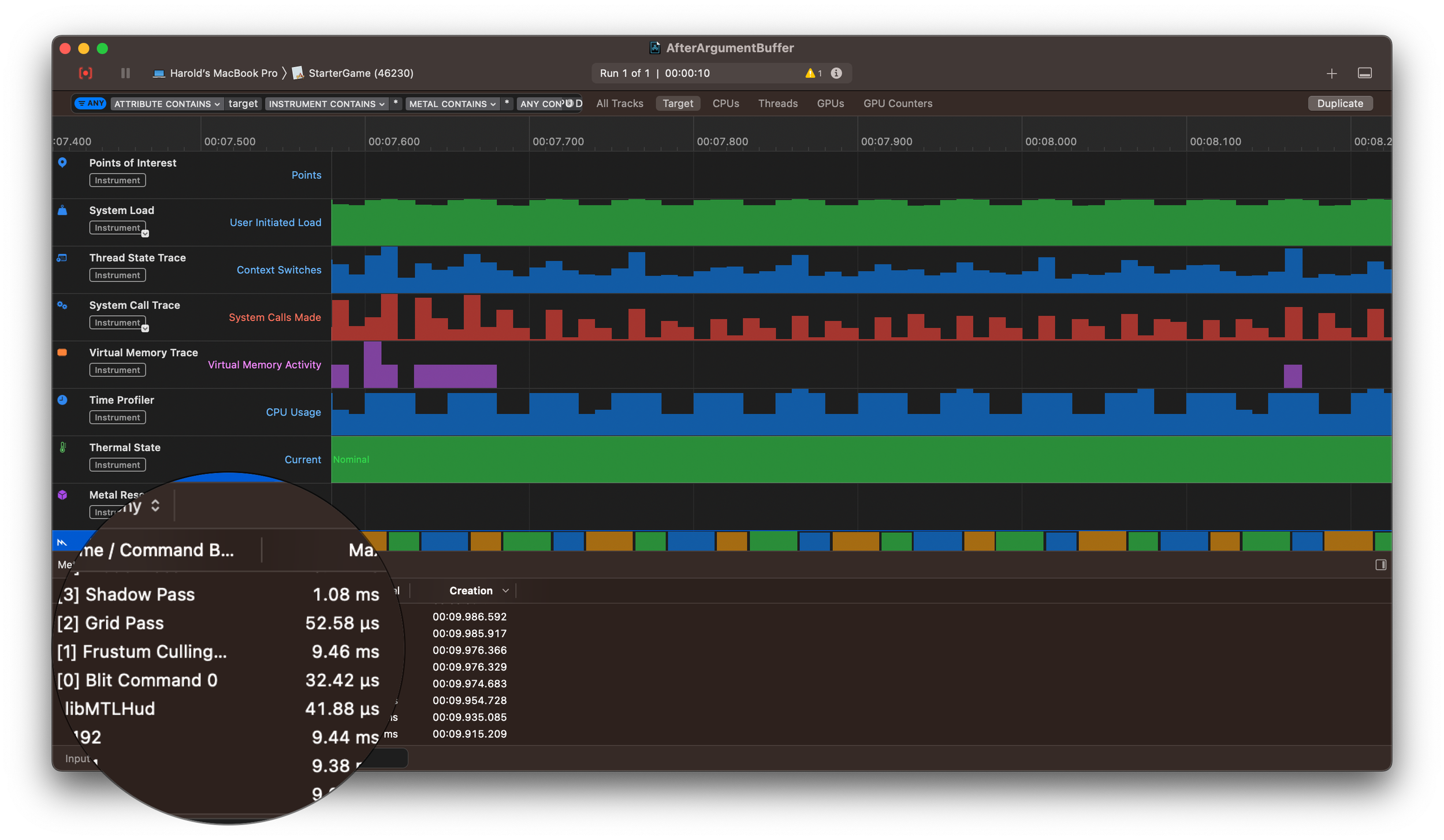

My engine’s editor runs asynchronously from the engine’s core functions. When I clicked the button to remove all entities, the editor tried to clear the scene immediately — even if those entities were still being processed by a kernel or the render graph.

In other words, the engine was destroying entities while they were still in use. That’s why systems started complaining about missing entities and missing components.

The Solution: A Mini Garbage Collector

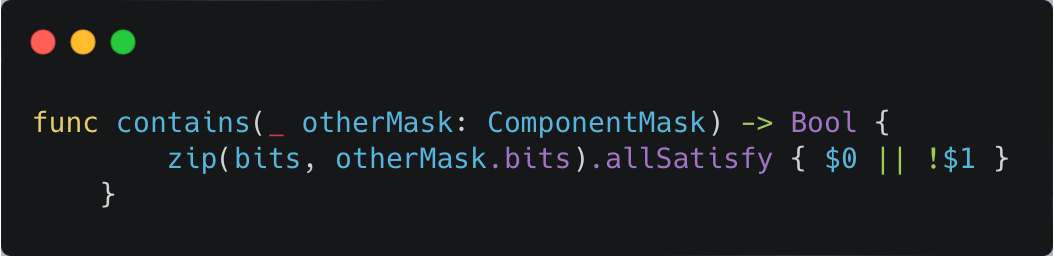

What I needed was a safe way to destroy entities. The fix was to implement a simple “garbage collector” for my ECS, with two phases:

- Mark Phase – Instead of destroying entities right away, I mark them as pendingDestroy.

- Sweep Phase – Once I know the command buffer has completed, I set a flag. In the next update() call, that flag triggers the sweep, where I finally destroy all entities that were marked.

This way, entity destruction only happens at a safe point in the loop, when nothing else is iterating over them.

Conclusion

What looked like a weird formatter bug turned out to be a timing bug in my engine. Immediate destruction was unsafe — the real fix was to defer destruction until the right time.

By adding a simple mark-and-sweep system, I now have a mini garbage collector for entities. It keeps the engine stable, avoids “entity does not exist” spam, and gives me confidence that clearing a scene won’t blow everything up mid-frame.

Thanks for reading.